The Kentucky Colonels in the mid-’60s. L-R: Leroy Mack, Roland White, Roger Bush, Clarence White & Billy Ray Lathum

1965 had to be bittersweet for Clarence White and the Kentucky Colonels. In February of that year, fiddler Scotty Stoneman joined the band for a half-year stint, transforming the Colonels into perhaps the greatest bluegrass group of all-time. If Clarence and Scotty weren’t the Bird and Diz of bluegrass, they were at least its Moon and Entwhistle. Unfortunately, the downside to that musical brilliance were diminishing paying gigs. By 1965, bands like The Beatles, Stones, and those local boys made good, The Byrds, had dramatically altered the cultural landscape. Clubs weren’t interested in booking bluegrass bands if they could get much more fashionable (and popular) rock bands.

Given this business environment, is it any surprise that Clarence White not only bought his first electric guitar, a 1954 Fender Telecaster, but convinced the other Colonels to plug in? By all accounts, his bandmates much preferred doing straight, old-time bluegrass. But, if the decision was between playing for pay or not playing for pay, I think even a staunch traditionalist could be forgiven for relenting.

Roland White, 1975

Photo: Jim McGuire“We went electric in the last year of the Colonels because we felt we had to. We’d gone through the folk boom thing, done the festivals, clubs, coffeehouses, and we never really got a good record deal. Clarence bought the Tele and then an amp, Billy Ray (Lathum) was on electric guitar, Roger (Bush) on electric bass, I had a little electric mandolin, and we got a drummer named Bart Haney. We had this gig, five or six nights a week in a lounge in a big bowling alley in Azusa (California) and we thought this was a good place to work things up. I think the place was called The Flame Room. We did some Johnny Rivers — I was playing ‘Memphis’ on mandolin! — and we played some Buck Owens things. We had to play the Top 20 because people wouldn’t dance to stuff they’d never heard. Roger sang ‘Memphis,’ I did more of the country stuff, and Clarence and I dueted on a few things we’d known since the 1950s, like the Louvin Brothers. We did three or four Beatles tunes, like ‘Ticket To Ride.’ A lot of their stuff reminded us of early country music, the way they sang, the harmonies. We used to do Everly tunes, too.”

–Roland White (brother to Clarence) in Tuff & Stringy: Clarence White Sessions 1966-68 liner notes

Mark that down, friends. In 1965, the Kentucky Colonels were officially playing country-rock. Where his bandmates may have reluctantly entered the rock era — let alone the country-rock era — Clarence dove in head first. As he explained in an interview published by Frets Magazine in July 1986, 13 years after his death, “It wasn’t so much that I was getting bored with acoustic bluegrass. I could feel so many new things in the air. I wanted to get in the stream of a new kind of music that combined what you could call a ‘folk integrity’ with electric rock.”

THE ZEKE MANNERS DEMOS

Which brings us to the Zeke Manners demos. Zeke passed away in October 2000 and was a peripheral figure on the LA scene for years, founding the west coast’s first hillbilly band, The Beverly Hill Billies, in the 1930s. In the ’60s, he served as musical director on the show of the same name and co-wrote “Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins,” which appeared on The Byrds’ Ballad Of Easy Rider album. (Incidentally, Manners was also the uncle of actor, director, and all-around comic genius, Albert Brooks, even appearing with his wife, Bea, in their nephew’s brilliant treatise on ’80s materialism, Lost In America.) Manners was a DJ at KFWBin L.A. when he met the Kentucky Colonels and persuaded them to record their electric demos at his home studio. Dating these recordings is damn near impossible, but my best guess is sometime between Fall 1965-Spring 1966. Though only 2 of the demos appear to have survived, they provide a unique window into Clarence White’s transition to the Telecaster.

Kentucky Colonels – Everybody Has One But You

Amazon

Written by Manners, “Everybody” is a Bakersfield country song by way of Lennon and McCartney, if not the Everly Brothers. Clarence’s guitar work is solid, if unspectacular, and the lead break is less country, more Keith Richards.

Kentucky Colonels – Made Of Stone

Amazon

“Made Of Stone” was written by Eric Weissberg, who Clarence probably met during the recording sessions for Weissberg’s 1963 album, New Dimensions In Banjo And Bluegrass, the album that would later evolve into the Deliverance soundtrack. Lyrically, “Stone” was perfect for Clarence to sing, what with his famous “statue-esque” stage presence. That’s why I’ve tacked on an intro taken from the Colonels’ great Livin’ In The Past album.

“Made Of Stone” is reminiscent of The Beatles, especially John Lennon songs of that era like “I’m A Loser” and “I Don’t Wanna Spoil The Party.” While certainly no classic, it is noteworthy for a couple reasons. First, playing harmonica is Clarence’s dad, Eric White, Sr. No less an authority than former bandmate, Gene Parsons, felt it was from Eric Sr. that Clarence got his sense of rhythm. As Gene says of Mr. White in the Byrds DVD, Under Review, “You could see where the White Family rhythm came from. It came from the old man, from old Eric. Boy, could he play the harmonica! He would do a clog dance while he was (playing).”

The second thing worth noting about “Stone” is Clarence’s entrance on guitar. As the elder White is holding his intro note on harmonica, you’ll hear a distinctive chime at the :20 mark. That was the famous “nut pull” that Clarence learned from James Burton. According to the fantastic liner notes on Tuff & Stringy, the nut pull involved “chiming a string at the 5th fret and then quickly pressing it down behind the nut, to produce a brief, high pitched note akin to a steel guitar.” This is significant because it was this effect that led directly to the B-Bender guitar. More on that later, but having mentioned Burton, it’s high time we established his role in Clarence White’s electric guitar transformation.

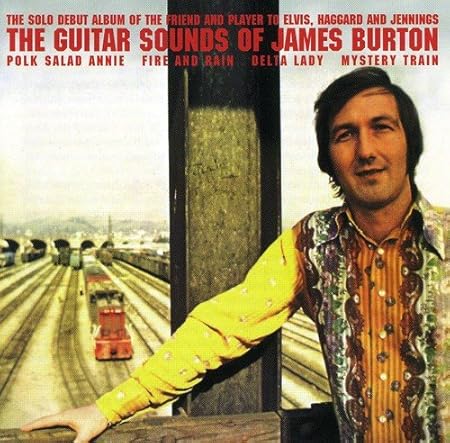

JAMES BURTON

James Burton is probably best known as Elvis‘ former guitarist and bandleader, having served as director of the TCB Band from 1969-77. He’s a towering figure in country and rock circles, his hotshot guitar rep beginning with Dale Hawkins‘ 1957 hit, “Suzie Q,” and solidified during a lengthy stint as Ricky Nelson‘s guitarist. Add years of gigantic, distinctive session work and there’s a reason why the King commanded his services. Here’s a video from what looks to be the ‘early to mid-’90s highlighting Burton’s chicken pickin’ brilliance, sense of innovation, and rhythm-heavy feel that held obvious appeal for Clarence.

Stars and Their Guitar: James Burton

Apparently, Burton heard Clarence play at one of the amplified Kentucky Colonel gigs and was suitably impressed. Shortly thereafter, in early 1966, Burton got Clarence his first session as an electric guitarist, playing with his old boss, Ricky Nelson. While Burton mostly played dobro, Clarence stretched his Tele wings for the first time, on the tracks that would make up the albums Bright Lights & Country Music (1966) and Country Fever (1967) — since reissued by Ace as a single two-fer disc.

Rick Nelson – Congratulations

Amazon

A few quotes from the Tuff & Stringy liner notes puts this era into perspective:

Roland White: “Clarence never said that he’d leave bluegrass behind, but you could see that it might happen. He’d wanted [pop stardom] for a long time, he’d even wanted that with us (the ‘electric’ Colonels). But he was making some money with sessions, whereas we (the Colonels) weren’t making any money.”

Gib Guilbeau, Clarence’s future bandmate in The Reasons (aka Nashville West): “Burton was Clarence’s idol. And James, in turn, admired his acoustic playing, so he sort of took him under his wing and showed him a bunch of stuff. Basically, Burton was Clarence’s tutor, showed him licks. Even got his Telecaster from James. He had the touch already, the fingerpicking, so it didn’t take him very long at all.”

Gene Parsons: “James was his mentor in going to electric, and they loved each other, but when Clarence started getting so good, James started to go, ‘Whooah, I don’t think I can give ya any more sessions!'”

GENE CLARK

A few quotes from the Tuff & Stringy liner notes puts this era into perspective:

Through most of ’66, Clarence kept busy with session work, nightclub gigs, and even a few dates with a reconstituted Kentucky Colonels. In October, he entered the studio with Gene Clark, who was cutting his first post-Byrds album. Gene Clark With The Gosdin Brothers leaned orchestral-pop way more than it did country-rock, but the twangy moments worked. No doubt, the talent helped. White joined a who’s who of country-rock pioneers, including Doug Dillard, Glen Campbell, Chris Hillman and Michael Clarke from The Byrds, and Rex and Vern Gosdin, who were bandmates with Hillman in his pre-Byrds bluegrass combo, The Hillmen.

Regarding the session musicians, Clark says in the album’s liner notes, “First came the Gosdin Brothers and Clarence White. The Byrds and the Gosdins had the same management, so we had been doing a lot of concerts together, especially in California. Clarence was playing guitar for them (the Gosdins), and their act was kind of country, just country enough for what I wanted to do, and Clarence came along with them.”

Gene Clark – Keep On Pushin’

Amazon

Clark said that his inspirations at the time were The Beatles, specifically Rubber Soul, and The Mamas & The Papas. That pretty much sums up “Pushin.'” The Clark-Gosdin harmonies are pure Phillips, but the music itself sounds like it was written with “I’ve Just Seen a Face” or “You Won’t See Me” in mind. The song showcases Doug Dillard’s electric banjo and Hillman’s sweet bass runs, but Clarence provides steady, behind the beat fingerpicking, deftly echoing Dillard’s banjo rolls. What the hell is that sliding sound on the outro that mirrors a doppler effect? A lovely kind of strange.

Gene Clark – Needing Someone

Amazon

Clark’s homage to George Harrison‘s “If I Needed Someone” brings the influence full circle, as Harrison wrote “Someone” with the early Byrds (featuring Clark) in mind. You can hear Clarence’s style coalescing as he brings his distinctive bluegrass chops to rock guitar. He toys with the beat and melody, winding his guitar around Hillman’s great walking bass. A killer sound and a fantastic, underrated song.

CHRIS HILLMAN + THE BYRDS

“I sort of grew up with Clarence. When I was in The Hillmen, we were always bumping into each other, but when I joined The Byrds I lost track of him for a couple of years. Then, around the end of ’66, I found him again, living way out of LA and playing in country groups in bars and things, playing electric guitar now. So we got him to help us on a couple of tracks. He played real good on them, too.”

–Chris Hillman in ZigZag, April 1973

As 1966 came to a close, The Byrds were in the studio recording songs for Younger Than Yesterday. Hillman, inspired by his recent session work with Letta Mbulu and Hugh Masekela, brought his first songwriting efforts to the studio. I don’t think there’s enough critical appreciation of Hillman’s artistic leap from Fifth Dimension to Younger Than Yesterday. He was an inventive, melodic bassist and provided great harmonies, but in a group with Roger/Jim McGuinn, Dave Crosby, and Gene Clark, he was a role player. He wrote ZERO Byrds songs prior to these sessions, only getting songwriting credits on instrumentals and folk rearrangements. And yet, on Younger he unleashed a murderer’s row of excellence: “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” (co-written w/McGuinn and featuring Masakela on trumpet), “Have You Seen Her Face,” “Thoughts And Words,” and two country songs, “Time Between” and “The Girl With No Name.” For the latter two, Hillman enlisted his old buddy Clarence to lay down the law. So, he did.

Byrds – Time Between

Amazon

Chris Hillman: “I got so excited coming out of (the Masekela) sessions that I wrote ‘Time Between,’ which had nothing to do groove-wise with what I’d been doing all day. It’s really like a bluegrass tune.”

Clarence, panned left, steals the show. The vocal harmonies and insistent right channel maraca is pure Beatles (or Sir Douglas Quintet, with whom The Byrds played many dates in 1965-66). White dominates the left channel, channeling Don Rich and then going way beyond Bakersfield. The solo from 1:13-1:31 is great, but his dive bomber run from :44-:58 is CW turning the corner and figuring out his electric guitar sound. In so doing, he also foreshadows his monster solo in “Tell Me.”

Byrds – The Girl With No Name

Amazon

Clarence enters on a nut pull and throws down more of his steel-influenced, behind-the-beat guitar work. In the bigger picture, CW’s presence legitimized The Byrds’ experiments in country music. And while no one could’ve known at the time, from here on out The Byrds would embrace country music, in no small part because Clarence White was on speed dial. And this relationship worked both ways. When Clarence was searching for his voice in the rock world, The Byrds offered him an early platform, and theirs would eventually mature into a full-fledged musical partnership. But, that was a couple years down the road.

Nearly simultaneous with the Younger Than Yesterday sessions, and at the same studio where Gene Clark With The Gosdin Brothers was being recorded, Clarence again entered the studio with his buddy Chris Hillman and Byrds drummer, Michael Clarke. Added to the roll call was steel player, Red Rhodes, who actually configured the pickups on Clarence’s Tele (the famous “Velvet Hammers”) and later built him a homemade fuzz box. On this occasion, the project was a single by The Gosdins themselves, spearheaded by Byrds producer, Jim Dickson.

Gosdin Brothers – One Hundred Years From Now

Amazon

While one of the songs, “No Matter Where You Go (There You Are)” was a pretty faithful Bakersfield rip, the other two songs are notable for different reasons. “One Hundred Years From Now” is NOT the Gram Parsons song that would appear on Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, but rather a Gosdins original. The song is dominated by Rhodes’ steel guitar and Rex and Vern’s vocal harmonies, but Clarence’s Tele is panned right and he adds understated color to the proceedings. Not a great song, but a good example of how folk, country, and rock were pretty much blurred together by late 1966.

Gosdin Brothers – Tell Me

Amazon

Alec Palao, producer of Tuff & Stringy and the mastermind of the Bakersfield International reissue program: “Clarence’s solo on ‘Tell Me’ is one of his greatest moments, in my opinion, and a very early example of his total prowess on the electric, as opposed to acoustic guitar.”

I think I’ve been helped by chronology, but I was saving the best for last regardless. “Tell Me” is Clarence’s earliest electric guitar showcase and if there were any lingering doubts as to his comfort with the Tele, this song doesn’t just clear them up, it goes all Bruce Lee one-inch-punch on them. It’s as if he distilled all that he’d learned from Joe Maphis and James Burton — not to mention the other great electric guitar influences percolating in his brain at the time — and perfectly integrated them with his bluegrass background. The final :50 in particular demonstrates a breathtaking sense of rhythm, a creative fearlessness, and a total command of his instrument. In the parlance of bebop, the dude is dropping bombs, one after the other, daring you to keep up.

What makes this awe-inspiring performance all the more remarkable — and not in a good way — was that it wasn’t even available to the public until the Gosdins’ CD, Sounds Of Goodbye was reissued in 2003. It’s like finding out last week that Jimi Hendrix recorded an obscure chestnut called “Machine Gun.” Are you kidding me? I can see how “Tell Me” might have been too experimental for the pop charts, but not releasing it in any form for over three decades?!?! And the music industry wonders why so many of us wish for its unhealthy demise. Regardless of that oversight, the performance has stood the test of time. In fact, I’m certain that one hundred years from now, our descendants will still be listening to that track and marveling at its stunning brilliance.

Awesome as usual! Some of the links on my post that you referenced were dead, so I have re-upped them.

Sorry about that, Paul. Didn’t mean to blindside ya ;) It was actually a last minute audible. I had “Time Between” and “Tried So Hard” queued up, but figured I should throw some bones your way after all the times you’ve sent folks here.

this goes beyond blog post to great resource. fine fine job.

Utterly absorbing….

So far, this series has been an absolute treasure (and I can only imagine it’s going to get better). Thanks–

chris

Just a quick line to add my vote of appreciation for the Clarence White series to those others who have already commented. Amazingly well researched and put together with particular attention to detail. Thanks.

Fab stuff – many thanks! I’ll be back!

yeah, killer post. I nabbed one of your photos for my post on Scotty Stoneman. Check it out

Love your site but can’t figure out how to access parts 3 4 5 etc of the Clarence White piece,

Please advise me on how to do this as I MUST read the rest of this story.

Thanks for the site. This is awesome. I’ve shared with 6 friends so far.

Hey Kim, thanks for writing, I certainly appreciate the love. Here’s those links.

Clarence White and the Rise of Nashville West: 1966-67 (Part 3)

http://www.adioslounge.com/clarence-white-and-the-rise-of-nashville-west-1966-67-part-3/

Clarence White: From Bakersfield To Byrdland: 1967-68 (Part 4)

http://www.adioslounge.com/clarence-white-from-bakersfield-to-byrdland-1967-68-part-4/

Clarence White: Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Men: 1968-69 (Part 5)

http://www.adioslounge.com/clarence-white-drug-store-truck-drivin-men-1968-69-part-5/